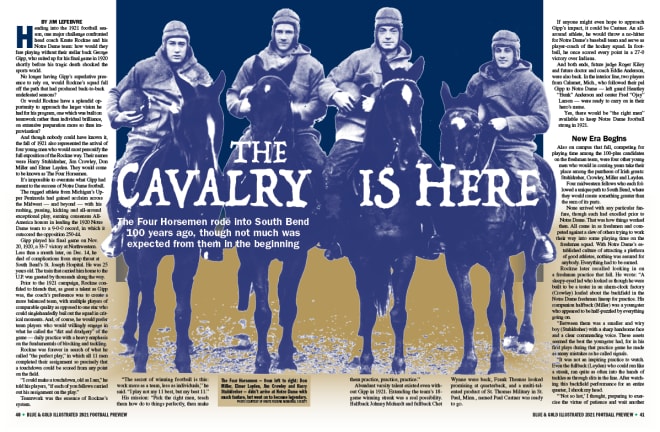

The Four Horsemen rode into South Bend 100 years ago, though not much was expected from them in the beginning

The following is an excerpt from the 2021 BGI Football Preview, available for purchase by clicking here.

Heading into the 1921 football season, one major challenge confronted head coach Knute Rockne and his Notre Dame team: how would they fare playing without their stellar back George Gipp, who suited up for his final game in 1920 shortly before his tragic death shocked the sports world.

No longer having Gipp’s superlative presence to rely on, would Rockne’s squad fall off the path that had produced back-to-back undefeated seasons?

Or would Rockne have a splendid opportunity to approach the larger vision he had for his program, one which was built on teamwork rather than individual brilliance, on extensive preparation more so than improvisation?

And though nobody could have known it, the fall of 1921 also represented the arrival of four young men who would most personify the full exposition of the Rockne way. Their names were Harry Stuhldreher, Jim Crowley, Don Miller and Elmer Layden. They would come to be known as The Four Horsemen.

It’s impossible to overstate what Gipp had meant to the success of Notre Dame football.

The rugged athlete from Michigan’s Upper Peninsula had gained acclaim across the Midwest — and beyond — with his rushing, passing, kicking and all-around exceptional play, earning consensus All-America honors in leading the 1920 Notre Dame team to a 9-0-0 record, in which it outscored the opposition 250-44.

Gipp played his final game on Nov. 20, 1920, a 33-7 victory at Northwestern. Less than a month later, on Dec. 14, he died of complications from strep throat at South Bend’s St. Joseph Hospital. He was 25 years old. The train that carried him home to the U.P. was greeted by thousands along the way.

Prior to the 1921 campaign, Rockne confided to friends that, as great a talent as Gipp was, the coach’s preference was to create a more balanced team, with multiple players of comparable quality as opposed to one star who could singlehandedly bail out the squad in critical moments. And, of course, he would prefer team players who would willingly engage in what he called the “dirt and drudgery” of the game — daily practice with a heavy emphasis on the fundamentals of blocking and tackling.

Rockne was forever in search of what he called “the perfect play,” in which all 11 men completed their assignment so precisely that a touchdown could be scored from any point on the field.

“I could make a touchdown, old as I am,” he told his players, “if each of you fellows carried out his assignment on the play.”

Teamwork was the essence of Rockne’s system.

“The secret of winning football is this: work more as a team, less as individuals,” he said. “I play not my 11 best, but my best 11.”

His mission: “Pick the right men, teach them how do to things perfectly, then make them practice, practice, practice.”

Abundant varsity talent existed even without Gipp in 1921. Extending the team’s 18-game winning streak was a real possibility. Halfback Johnny Mohardt and fullback Chet Wynne were back, Frank Thomas looked promising at quarterback, and a multi-talented product of St. Thomas Military in St. Paul, Minn., named Paul Castner was ready to go.

If anyone might even hope to approach Gipp’s impact, it could be Castner. An all-around athlete, he would throw a no-hitter for Notre Dame’s baseball team and serve as player-coach of the hockey squad. In football, he once scored every point in a 27-0 victory over Indiana.

And both ends, future judge Roger Kiley and future doctor and coach Eddie Anderson, were also back. In the interior line, two players from Calumet, Mich., who followed their pal Gipp to Notre Dame — left guard Heartley “Hunk” Anderson and center Fred “Ojay” Larson — were ready to carry on in their hero’s name.

Yes, there would be “the right men” available to keep Notre Dame football strong in 1921.

New Era Begins

Also on campus that fall, competing for playing time among the 100-plus candidates on the freshman team, were four other young men who would in coming years take their place among the pantheon of Irish greats: Stuhldreher, Crowley, Miller and Layden.

Four midwestern fellows who each followed a unique path to South Bend, where they would create something greater than the sum of its parts.

None arrived with any particular fanfare, though each had excelled prior to Notre Dame. That was how things worked then. All came in as freshmen and competed against a slew of others trying to work their way into some playing time on the freshman squad. With Notre Dame’s established culture of attracting a plethora of good athletes, nothing was assured for anybody. Everything had to be earned.

Rockne later recalled looking in on a freshman practice that fall. He wrote: “A sleepy-eyed lad who looked as though he were built to be a tester in an alarm-clock factory (Crowley) loafed about the backfield in the Notre Dame freshman lineup for practice. His companion halfback (Miller) was a youngster who appeared to be half-puzzled by everything going on.

“Between them was a smaller and wiry boy (Stuhldreher) with a sharp handsome face and a clear commanding voice. These assets seemed the best the youngster had, for in his first plays during that practice game he made as many mistakes as he called signals.

“It was not an inspiring practice to watch. Even the fullback (Layden) who could run like a streak, ran quite as often into the hands of tackles as through slits in the line. After watching this backfield performance for an entire quarter, I shook my head.

“‘Not so hot,’ I thought, preparing to exercise the virtue of patience and wait another year for a sensation like George Gipp. This freshman bunch could be whipped into a combination of average players. Not much more.”

Even accounting for some hyperbole on the coach’s part, it was clear the four had some tough days in their initial fall on the Notre Dame campus. The freshman team lost games to Lake Forest Academy and the Michigan Aggies frosh, worrying signals for the seasons to come.

Yet each of the four seemed destined to be at Notre Dame in the fall of 1921.

The Little General

Rockne once famously hosted an event for the New York press at a grain scale in New Jersey, at which each of the Four Horsemen was weighed, to debunk reports that Notre Dame was exaggerating just how small they were. And it proved that none weighed in at more than 162 pounds.

Easily the smallest of the four was Stuhldreher (5-7, 151), a quarterback who was less than 140 pounds when he started his senior year of high school in football-crazed Massillon, Ohio, in 1919.

Stuhldreher had grown up being teased for his small stature, but managed to snare a starting halfback spot for Massillon. Early in the season, an injury sidelined the starting quarterback and he became the signal-caller, with mixed results. For the big season finale against archrival Canton McKinley, he had to watch from the sidelines with an arm injury.

His older brother Walter, much to their mother’s joy, was already a Notre Dame student. Although not an athlete, Water served in the school’s Naval Unit until the Armistice ended the Great War on Nov. 11, 1918.

In Stuhldreher’s case, it was decided he needed another year of seasoning, both academically and athletically, before attempting college. For the 1920-21 school year, he was enrolled at the Kiskiminetas Springs School, known as Kiski Prep, about 50 miles east of Pittsburgh. At Kiski, Harry sharpened his grades, excelled at quarterback and won the admiration of fellow students and faculty.

A Football Family

Across the state, in northwest Ohio, one particular family was making a name for itself in football. The oldest of Martin and Anne Miller’s six sons, Harry “Red” Miller starred for one of Defiance High School’s first teams and enrolled at Notre Dame in 1906. Red was a four-year starter at left halfback, and in 1909 played a key role in Notre Dame’s historic 11-3 victory over Michigan, ending a skein of eight losses in the first eight games against the Wolverines.

Red was followed by brothers Ray and Walter; Ray was a backup end behind Rockne in 1911-12, while Walter started at halfback alongside Gipp in 1917.

In 1921, Don Miller — a 5-11, 160-pound halfback — enrolled along with older brother Gerry, who had missed some school because of health issues. Gerry was considered the stronger bet to carry on the family tradition, with a flamboyant running style that wowed observers. And indeed, it was Gerry whose dizzying moves resulted in three touchdowns in freshman-team victories over Culver Academy and Great Lakes.

That first fall for Don, meanwhile, was disheartening. When the Notre Dame football togs were distributed to the entire team, he received mere scraps. But, true to his down-to-earth nature and stoic work ethic, he swallowed his disappointment. He would prove himself with relentless practice, improving daily and setting the stage for the years ahead.

Sleepy Jim

By 1920, the town of Green Bay, Wis., was well established as a hotbed of football. One of its native sons, Earl “Curly” Lambeau, had starred at East High School, then played one season at Notre Dame in 1918, Rockne’s first as head coach. Lambeau lined up in the backfield alongside Gipp and scored the first touchdown of the Rockne Era, on Sept. 28. 1918, against Case Tech in Cleveland.

After that one season, truncated by the Great War and the influenza pandemic, Lambeau returned to his hometown and did what he did best — organize football teams. And when he induced his employer, the Indian Packing Company, to donate $500 for uniforms in the summer of 1919, the Green Bay Packers were born.

In addition to being co-founder and player-coach of the Packers, Lambeau coached at East High, where the star player was Crowley, who belied his drowsy appearance with dashes of brilliance on the gridiron.

Besides Lambeau, Crowley fell into the orbit of another former Notre Dame athlete. Bobby Lynch was a four-year ND baseball player who hopped across the country in minor league ball, landing as manager of the Green Bay team in 1913. He operated a combination billiards hall and sporting goods store, which blended two of Crowley’s favorite pursuits.

“Sleepy Jim” — a 5-11, 162-pound tailback — was known for his keen wit and as a jokester who could trade insults with the best of them, never appearing to take anything very seriously. But when selecting a college destination, it was clear to Crowley — Notre Dame was where he needed to test his athletic mettle.

Longing For Home

Layden looked the part of an athlete. Well-proportioned, with a square jaw and jet-black hair parted in the middle, he struck a handsome pose and drew the attention of young ladies in his hometown of Davenport, Iowa, and elsewhere.

At Davenport High, Layden starred as a darting fullback, a track sprinter and a basketball sharpshooter. At the famous Drake Relays, he teamed with his brother Clarence and two other pals to set the high-school record for the half-mile relay. He was set to attend the University of Iowa on a basketball scholarship before a knee injury caused the Hawkeyes to lose interest.

Meanwhile, Layden’s high school coach, Walter Halas, had joined the Notre Dame coaching staff as football assistant and head basketball coach. Halas was from a notable sporting family, his older brother George, a multi-sport star, had founded the Decatur Staleys, the team that eventually became the Chicago Bears, Lambeau’s greatest rival.

Layden followed Halas to Notre Dame and was desperately homesick as soon as he arrived. He would find ways to show up at the train station to “look up timetables.” But he never boarded a train, and when he was invited to dinner at Halas’ house, there was a surprise visitor, Rockne. Many topics were covered during their lengthy chat, including Layden’s homesickness. Rockne told him things would improve and boasted, “We’ve never lost a freshman from our team yet.”

Whether that was true or not, the talk influenced Layden to stay and give Notre Dame his best effort. It would not go unrewarded.

Epilogue

A seriously undersized quarterback. One halfback who was more of a jokester, another who was a football afterthought in his own family. And a fullback more intent on skipping town than breaking runs. That was the state of the Four Horsemen in the fall of 1921.

Within the next year, though, they would make the varsity, earn starting roles and begin a ride into football immortality.

As sophomores in 1922, Stuhldreher at quarterback, and Crowley and Miller at halfback gradually surpassed more experienced players to become starters for Notre Dame. Layden labored primarily in a reserve halfback role.

Then, in a 31-3 win over Butler in Indianapolis on Nov. 18, Castner — the captain and starting fullback — broke his hip. Rockne tabbed Layden as the new starter, telling him he would be a new type of fullback at 162 pounds — sleek and swift, able to gain yardage on quick opening plays.

The foursome would start together through the next two-plus seasons, compiling an overall record of 20-2. Both losses were to Nebraska in games at Lincoln, 14-6 in the 1922 finale and 14-7 on Nov. 10, 1923. After the second loss, the backfield would lead Notre Dame to 13 straight victories and widespread national recognition, culminating in a 10-0 record in 1924, a Rose Bowl victory and the school’s first consensus national championship.

The backfield’s effectiveness sprung from the versatility of each player. From the Notre Dame shift, the snap from center could be directed to any of the four, who then presented a threat to run, hand off, pitch out or drop back to pass. The possibilities were dizzying and kept defenses off balance.

For their careers, Miller led the quartet in rushing with 1,933 yards, followed by Crowley (1,841) and Layden (1,296). Stuhldreher completed 43 of 67 pass attempts for 744 yards with 10 touchdowns, but Crowley was the more frequent passer, connecting on 37 of 83 throws for 544 yards with four touchdowns. Miller had the most pass receptions with 31, followed by Stuhldreher (18), Crowley (13) and Layden (11). Layden did most of the punting, and he and Crowley shared extra-point duties.

Surprisingly, at just 151 pounds, Stuhldreher was considered the most effective blocker.

In career scoring, Crowley led the way with 144 points, followed by Miller (132), Layden (96) and Stuhldreher (74). As a team from 1922-24, Notre Dame outscored the opposition 782-118 en route to going 27-2-1 overall.

As seniors in 1924, the group traveled to New York City for Notre Dame’s annual game with archrival Army on Oct 18. In front of a packed house of 55,000 at the Polo Grounds, Rockne’s men engaged in a classic tussle with the Cadets, eventually controlling the game with a series of long, ball-possession drives on the way to a 13-7 victory.

Afterward, the nation’s most prominent sportswriter, Grantland Rice of the New York Herald Tribune, wrote: “Outlined against a blue-gray October sky, the Four Horsemen rode again. In dramatic lore, they are known as famine, pestilence, destruction and death. These are only aliases. Their real names at Stuhldreher, Miller, Crowley and Layden.”

Later, student publicity aide George Strickler arranged for the four to be photographed atop local work horses in South Bend, and before long, the image and nickname gained wide popularly nationwide.

But there was still most of a season to play, against an array of top teams. Princeton, only two years removed from its own national title. Georgia Tech, the strength of the South. Western Conference challengers Wisconsin and Northwestern. And the old nemesis Nebraska. This time, though, the Cornhuskers would visit Cartier Field, and with each of the Horsemen scoring a touchdown (and Miller two), the Irish prevailed 34-6.

The team made an epic, three-week trip to and from the Rose Bowl on Jan. 1, 1925. There, against a mighty Stanford team coached by Pop Warner and led by the great Ernie Nevers, the Irish were outgained but scored three defensive touchdowns, including two long interception returns by Layden, and won 27-10 to secure the 10-0 season and national championship.

All four of the Horsemen subsequently gained induction into the College Football Hall of Fame — Layden in 1951, Stuhldreher in 1958, Crowley in 1966 and Miller in 1970.

Jim Lefebvre is co-founder and executive director of the Knute Rockne Memorial Society (www.RockneSociety.org) and author of two award-winning books on Notre Dame football, Coach For A Nation: The Life and Times of Knute Rockne and Loyal Sons: The Story of The Four Horsemen and Notre Dame Football’s 1924 Champions. Have a question about Fighting Irish football history you’d like explored? Email: Jim@NDFootballHistory.com.

----

• Learn more about our print and digital publication, Blue & Gold Illustrated.

• Watch our videos and subscribe to our YouTube channel.

• Sign up for Blue & Gold's news alerts and daily newsletter.

• Subscribe to our podcast on Apple Podcasts.

• Follow us on Twitter: @BGINews, @Rivals_Singer, @PatrickEngel_, @tbhorka and @ToddBurlage.

• Like us on Facebook.