A Notre Dame Spirit To Emulate

It’s unlikely that any generation of football fans could be more blessed than Notre Dame's were throughout the 20th century.

Four generations witnessed the passing of the baton from one titan to another, with some leaner years interspersed in between perhaps to seemingly keep the base honest and better appreciate the future glory.

The festivities commenced with Knute Rockne's (1918-30) three consensus national titles, two other unbeaten seasons and the best winning percentage to this day in major college football history.

The ensuing generation had Frank Leahy (1941-43, 1946-53), who posted six unbeaten campaigns, four consensus national titles and the second-best winning percentage in history, behind Rockne.

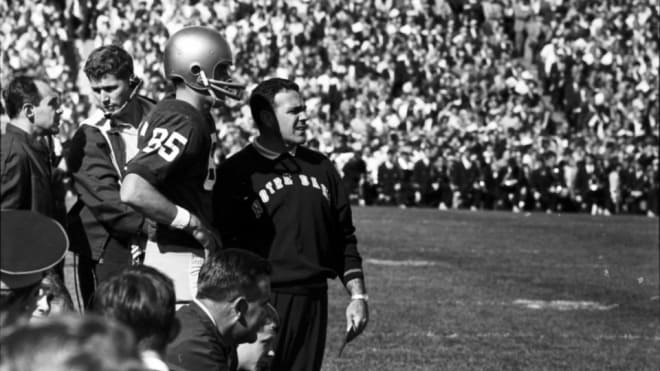

And just when it looked like Notre Dame had used up its quota of colossus coaches in its lifetime and the football well had run dry, along came Ara Parseghian (1964-74) to provide renewed baptism and ultimate resurrection in one fell swoop as the proverbial "Messiah Coach." His 11 seasons produced two consensus national titles, a share of another in a third and a .8362 winning percentage.

Since Parseghian’s arrival in 1964, the only major college football coaches who won a better percentage with at least 10 years at the same school are Alabama’s Nick Saban at .857 in the 10 years from 2007-16 and Oklahoma’s Barry Switzer — .8368 from 1973-88.

Even the symmetry is amazing. Rockne was hired in 1918, followed by Leahy 23 years later (1941) — and then Parseghian 23 years later again (1964). Lou Holtz (1986-96) eventually rounded out the Mount Rushmore of Fighting Irish coaches in the 20th century (although he “broke” the perfect symmetry while getting hired 22 years later, not 23)

Each coach mirrored the presidents whose faces are immortalized on Rushmore.

George Washington/Rockne guided “The Union” into eminence, while Thomas Jefferson/Leahy steered a marvelous expansion of it.

Then it was Lincoln who saved The Union while guiding the nation through its darkest days in The Civil War (1861-65). Likewise, it was Parseghian who saved Notre Dame football, which had endured its nadir from 1956-63. The squad was 34-45 during that time, including 2-8 in both 1956 and 1960, and 2-7 the year before his first season in 1964. During the tumultuous times, there was a perceived “civil war” at the school between academics and athletics. (Lou Holtz in 1986-96 would represent marvelous orator and rough rider Teddy Roosevelt, but that’s another story for another time).

Parseghian arrived when the perception was that the program was living on the perfume of a vanished rose — not unlike today: College football’s landscape had changed forever. The dynasty days for Notre Dame were over. The academics were too demanding. The school rules were archaic, if not draconian. Top recruits weren’t attracted to a non-coed school (until 1972), and star black players didn't want to enroll at a small, Midwest, private, Catholic school with few minorities. The schedule also was too treacherous…

Shepherded by Parseghian, the dying ember that was Notre Dame football was relit with a roaring inferno. Highly photogenic and mesmerizingly charismatic — you can’t spell aura without Ara — he became more even more esteemed and better defined as a man than a football coach.

Few ever in college football inspired greater universal respect and more fierce loyalty than Parseghian, whose yearly salary was going to top out at $35,000 his final season. That was a plenty good living in northern Indiana in that time, but he also was known to split his earnings from his television show or through speaking engagements among all his assistants. An assistant making $14,000 per year would sometime receive about half that from Parseghian’s own pocket as a year-end bonus (something Parseghian would not confirm or delve into when asked about it).

I began following Notre Dame football as an 8-year-old in 1970, the third generation that grew up with “the fever” and lore that was handed down and cultivated. It was the back end of the Era of Ara — and one that began to raise angst that his best days were behind him.

In 1971, his Irish were the preseason favorites to win the national title, but the 8-2 season was so disappointing, the team voted to turn down a bowl game to not prolong the “misery.” The two losses — 28-14 to USC and 28-8 at LSU in the finale — were the “big ones” on the schedule.

Then in 1972, Parseghian experienced his first defeat as a heavy home favorite, 30-26 to a Missouri team that a week earlier had lost 62-0 to Nebraska. The campaign ended with a 45-23 drubbing at No. 1 USC, and then an epic 40-6 collapse to Nebraska in the Orange Bowl, his worst defeat at Notre Dame. It was also the first time in his nine seasons the Irish lost three games.

It was the era of “Ara can’t win the big one.” He was 0-4-2 against arch rival USC from 1967-72, and top-10 Purdue vanquished him three straight years from 1967-69 in game 2 to quickly squelch national title hopes he had revived. Even after winning the 1966 national title, the 10-10 tie with No. 2 Michigan State led to vilification that would gain momentum.

The year before Parseghian’s arrival, Notre Dame had lost eight straight to Michigan State, five of the last six to Purdue, four of the last six to Pitt, three of the last four to Navy — and it was even 0-4 against his teams at Northwestern.

When the Fighting Irish dispatched of those teams under his watch, they were ridiculed for playing “easy schedules.”

“The 'big one' is usually any game you lose,” he said with a chuckle a few decades ago in one of my first interviews with him.

Then in 1973, a perfect 11-0 Notre Dame team captured yet another national title, and the legend flourished and continued.

In 1974, I read a statement by him that remains a mantra: “Adversity elicits talent which under prosperous conditions would have remained dormant.”

It was so wonderfully eloquent — even though as a pre-teen I had no idea what it meant — that it stayed with me forever. As an adult, it further served as inspiration during the trying patches through life.

It wasn’t until 1992 that I began my own tradition of interviewing Parseghian on a yearly basis, until the past couple of years. It was embarrassing to be so knock-kneed and nervous about meeting him face-to-face the first time at age 30, yet he possessed a remarkable trait to make you feel at ease. He epitomized Rudyard Kipling’s poem “If” about walking amongst kings yet keeping the common touch.

What intrigued me during the interviews is he often didn't remember or was sketchy about certain parts of his 95 victories. But among his 17 losses and four ties he could recite the most minute of details — a missed block here, a wrong signal there, etc. — about virtually every single play from the game.

His long-time assistant and right-hand man, Tom Pagna, told me once that if Parseghian had a weakness, it was that he had difficulties putting a loss behind him, and he would pore over tape for hours on end dissecting any wrong move he made. He would agonize about it, which helped hasten his coaching departure by the age of 51, when most are just beginning to hit their peak.

Far greater anguish and tragedy often trailed Parseghian in his last 50 years. In November 1994, two months after learning that three of their four children had a rare, fatal, genetic disease called Niemann-Pick Type C (NP-C), Cindy and Dr. Michael Parseghian (his son), plus a cadre of volunteers, founded the Ara Parseghian Medical Research Foundation that the then 71-year-old Parseghian invested into with all his mind, heart and soul.

Back in 1967, Parseghian was devastated when his oldest daughter, Karan — whom he out-lived — was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Despite his hectic schedule at Notre Dame, Parseghian became chairman of the National MS Foundation, and his experience in that endeavor helped him raise awareness and fund a potential cure for NP-C.

The valiant efforts weren’t enough to save Cindy and Michael’s three youngest children. Michael Jr., 9, lost his battle in 1997. Christa, 10, passed away in 2001. Marcia, 16, died in 2005.

“We’re all scarred from this experience,” said the eldest Parseghian several years ago in one of my final interviews with him. “I would be driving in the car by myself and I would break down. Here are two wonderful parents that are raising their children in the proper American way, wonderful human beings – why would this happen to them, and why did the poor grandchildren have to go through it? That I can’t understand and never will be able to.”

Even then, his fighting spirit never departed.

“There’s no question being involved with competitive athletics has helped me with this,” Parseghian said. “You get knocked down, you have to get up, particularly in football because the very nature of the game is physical, mental, strategic, emotional...

“Do I have faith we’re going to find a solution? Yes. Did we get the silver bullet before our grandchildren were gone? No, but we’re still hopeful of finding a cure so other parents and grandparents and children won’t have to suffer under this agony of this doggone disease.”

He confessed that it elicited questions about his own faith.

“There are days I pick up the newspaper and see some tragic event that has occurred and wonder why,” he said. “I don’t know if pastors or priests or ministers can totally explain some of these situations that seem to be so unfair. Yeah, you’re challenged with your faith — but you don’t let it affect what you find as your cause and the need for a hopeful solution.”

At times during the 21st century I have mused whether the football gods have said, “Notre Dame had its time in the 20th century; it’s time for others to thrive now.”

And then you think of the legacy of Parseghian and others who brought such honor to the school… and dare to not let such a spirit, on or off ny field, die.

----

• Talk about it inside Rockne's Roundtable

• Subscribe to our podcast on iTunes

• Learn more about our print and digital publication, Blue & Gold Illustrated.

• Follow us on Twitter: @BGINews, @BGI_LouSomogyi, @BGI_CoachD,

@BGI_MattJones, @BGI_DMcKinney and @BGI_CoreyBodden.

• Like us on Facebook